Title: Investing the Templeton Way: The Market-Beating Strategies of Value Investing’s Legendary Bargain Hunter

Author: Lauren C. Templeton, Scott Philips

Published: 2008

Buy the book here: Saxo.com or amazon.de

Why should I read it?

Legendary fund manager Sir John Templeton has been called “the greatest stock picker of the century” by Money magazine and is widely recognized as one of the pioneers of global investing. Templeton has beaten all the major indices over an impressive period of over 50 years.

The book offers a fine balance between the strategies and methods that set Templeton apart from other investors, practical recommendations for identifying and analyzing investments, and a number of concrete examples from his own career.

The book can be read by anyone interested in the art of identifying and analyzing specific investments and is highly recommended.

Sir John Templeton (b. 1912)

John Templeton was born in Winchester, Tennesee, USA and attended Yale University, where he financed part of his expenses with poker winnings.

He graduated in 1934 and went on to earn an M.A. in Law at Oxford University and later studied under the father of value investing, Benjamin Graham.

Templeton became a billionaire with the launch of his pioneering globally diversified mutual funds, including the Templeton Growth Fund in 1954 and the company went public in 1959.

The man behind the name: Investing is a lifestyle

Before we dive into Templeton’s approach and techniques for investing, it’s worth briefly rewinding to his upbringing in 1920s Winchester, USA. After all, how do you end up as one of the most successful and wealthy investors of the last fifty years?

As a child, Templeton’s father, Harvey Sr. Solicitor with an office in Winchester’s town square overlooking the courthouse. During the 1920s in the US, many of the area’s farmers faced financial difficulties and several ended up with personal bankruptcy and foreclosure of their property. Here, Harvey Sr. sit in the office and keep an eye on the auctions in the market square. When there was an auction but no buyers, he would go down to the market square and make a very low bid. With no other buyers, he often got the land for a price that was much lower than their actual value. That this could be the case may be surprising today, but there have been many similar situations later in Templeton’s own career as a portfolio manager.

Templeton’s investment philosophy is fundamentally based on the approach his father took when buying foreclosed properties. Stock markets are essentially large auction houses, and if you’re one of the only buyers, you can buy shares at very attractive prices. This is actually one of the great ironies of the stock market – when a stock falls in price, it attracts fewer buyers, while a stock that rises in price will experience a corresponding increase in popularity.

The other main reason for Templeton’s later wealth was his frugality. A skill that both he and his older brother shared throughout their lives. Despite their father’s repeated success in investing in country properties, he was very risk-averse with the gains. Among other things, he invested the returns in cotton futures on the New York and New Orleans exchanges. Here they heard their father proudly tell them “Boys, we’ve made it rich, we just made more money than you can imagine in the cotton futures market, you will never have to work another day in your lives, neither will your children or grandchildren” The two brothers were excited, but it was only a few days before their father came home one night and told “Boys, we’ve lost it all; we’re ruined“.

This approach to investing and finance was something neither brother wanted to repeat, so frugality became a fundamental principle. Early in his career, Templeton decided that For every every penny he and his wife earned, they would save 50 cents and invest. They did this by buying virtually everything second-hand. Preferably high quality, but from sellers who didn’t care too much about price or who had no other buyers.

Similarly, it became a principle that he bought everything in cash and therefore would always be a receiver of interest, never a payer of interest. He never had a car loan, bank loan or bond in the house.

The point of maximal pessimism

Early in his career, Templeton studied under the father of value investing, Benjamin Graham, at Columbia University. Graham’s principles resonated well with Templeton’s own experiences growing up, but Graham typically looked for so-called ‘cigar butts’, which are basically companies in liquidation at an extremely low price, Templeton often focused on quality, but at a low price relative to the company’s fundamental value. In Templeton’s view, this means that a company should ideally trade at 20 cents for every 1 krone of value. It’s not easy to find and requires patience and discipline.

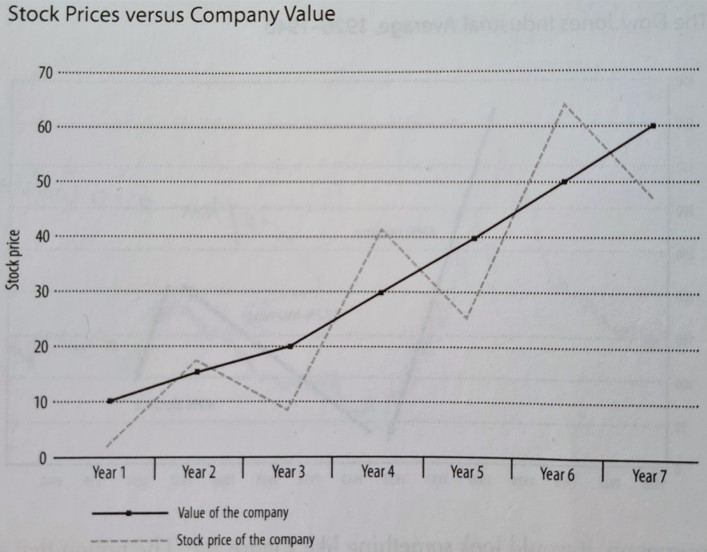

A good illustration of this principle can be seen below. A company’s price will fluctuate from time to time, often due to factors that are either not directly relevant to the company, such as the industry no longer being as popular in the media, or because the company is experiencing temporary problems and the market is overreacting. Both situations can be advantageous times for a bargain hunter to buy up.

In Templeton’s view, there is only one reason for a stock to sell at a low price: other investors are selling. But regardless of what the market is telling you at any given time, every investor’s goal should be to buy as much earnings power as possible at as low a price as possible. In more practical terms, it means buying a company with growing revenue and earnings at a low price (e.g. P/E or EV/EBIT). And how do we find such companies? If we ask Templeton, the answer is:

People are always asking me where the outlook is good, but that’s the wrong question. The right question is: Where is the outlook most miserable?”

In order to take advantage of these types of situations, we as investors must

- Study the situation before it happens. As we all know, no one can predict the future, but there are many future scenarios that we are very likely to experience and can expect to play out. All companies experience rainy days – when a product launch fails, earnings don’t meet market expectations or the entire stock market takes a major or minor correction. Here, the long-term investor should have a ‘watchlist’ of interesting companies that have already been analyzed and available funds to take advantage of a given market correction.

- Understand the company’s business thoroughly before we buy the stock. How does the business work, what drives sales activity, what risks can limit earnings, where is the position against competitors, etc. Without this knowledge, we can’t really distinguish between the challenges that are temporary and those that are permanent. It will also give us the mental strength to stick to our decision and investment if- (and in practice often

when the

– the price of the company we own continues to fall.

This approach is why investors like Templeton and Buffett can make big investment decisions in a matter of hours when the opportunity arises.

Go bargain hunting with Templeton

Over the past 30 years, the growth in global investing has given work to more and more analysts, all of whom evaluate and publish an ever-increasing number of analyses and forecasts. Similarly, technological developments have made it a simple matter to find data on companies that previously could take hours, days or even weeks to obtain.

Despite this increased efficiency and transparency in the markets, there is still a rich supply of stocks that have no or very few analysts assigned to them. Companies in less popular markets and geographies, as well as small and medium-sized companies, are excellent hunting grounds for a bargain hunter who is willing to put in the extra effort and do original bottom-up analysis of specific companies.

With this in mind, the obvious question becomes – how do we find the right companies to analyze? Below are the most important characteristics:

- While it may sound simplistic, one of Templeton’s most commonly used ratios to find companies and give a rough price indication was the company’s P/E (i.e. share price divided by earnings per share). Obviously, we can’t go out and buy every company with a low P/E, but it’s a reasonable premise to pay as little as possible for a company’s future earnings. Many examples from Templeton’s career show that he bought companies with exceptionally low P/Es between 2 and 5. Typically in countries that had fallen out of favor with investors, such as Japan in the 1960s or South Korea in the 1990s.

- To increase the quality of this simple filter, Templeton introduced a principle of looking for stocks that sell for less than five times the current share price divided by our estimate of earnings (EPS) in 5 years. Estimating a company’s EPS in 5 years is not a simple task, but the basic approach should be to look at the company’s average historical performance and adjust for any significant changes in the company’s or sector’s future prospects. Or to put it another way: if the net profit margin over the last 10 years has averaged 5 percent, but the company has increased this to 7 percent in the last year, a reasonable investor should use 5 percent. This will provide a margin of safety for an estimation that is difficult in practice. This approach is interesting because it forces us to think about the future development of the business itself over a time horizon that is difficult, but not impossible, to estimate fairly.

- In a market in 2021 where many sectors have a P/E above 15 and even more above 20, it may seem unrealistic to find companies that meet this requirement. But they do exist if we’re creative. For example, some companies in China are down around this level, such as China Mobile. The company currently has a forward P/E of around 7, but if we adjust for their almost EUR 60 billion in revenue, the forward P/E is around 7. If we add USD 1.5 billion in cash and limited debt, we end up at around P/E 5. If we then add earnings growth (the E in calculations) of around 3%, we end up with a P/E of around 4.3, which is within Templeton’s limit.

“There is no reward for getting the fundamentals right if they already are built into the stock price. As a bargain hunter, you should be focused on extreme mismatches between the way a stock is priced and what it is worth, not simple nuances.”

The 100 measures of value

While corporate earnings were the primary metric for Templeton, his approach was to use what he called “the 100 yardsticks of value” in our hunt for companies that are priced below their fundamental value. This can be P/E, Price/Earnings to Growth (PEG), which also takes into account the company’s growth, or Price/Book, which is the price compared to the company’s book value.

His starting point was that if we limit ourselves to one specific method for finding and valuing stocks, we will sometimes experience long periods of time where our method doesn’t work. Another important reason is that using several different types of metrics gives us an opportunity to increase (or decrease) our conviction that a given stock is a good buy. The important point here is that no key figures can be used in isolation. Each metric has its pros and cons and should be interpreted to understand what it indicates. Similarly, different ratios will be more or less accurate depending on the sector, e.g. P/B may be a reasonable measure for banks, but is difficult to use for technology companies, which often have a large amount of goodwill but few physical and financial assets. Similarly, a company’s ratios should be compared to the historical ratios over the last 5 and 10 years.

And what yardsticks did Templeton use in practice? In addition to the above-mentioned ratios such as P/E, P/B and PEG, he used a wide range of interesting factors and ratios to assess whether a company’s price was actually down to the 20 øre for every 1 krone of value. Below are the yardsticks Templeton often used:

- Assessing the replacement cost of a company’s assets, i.e. the replacement cost. Book value is the historical price, e.g. of real estate or a factory built 10 or 20 years ago, but not the replacement cost. For example, if there has been a significant increase in the price of real estate in the area or if there has been high inflation during the period, the book value will not be a fair proxy for the real value. In other words, there may be hidden value here that is not accounted for by the market.

- Knowledge of relevant business transferswhich is ongoing in the sector in question. The sale price of a company in a given industry or sector provides an insight into the ratios that the market was willing to pay to hold a majority stake in a company. This can be used as another measure of value. If a company in the industry is acquired by a competitor at, for example, a P/E of 17 and P/B of 3, this can be used as a benchmark for other companies in the same industry with similar characteristics.

- Templeton took the M&A mindset further by using companies’ ‘Enterprise Value‘ rather than the pure share price (‘price’). Enterprise Value takes the market cap (i.e. share price times number of shares) plus the company’s total debt and subtracts contacts. In other words, it is the price a buyer would have to pay if the entire company were to be transferred in a trade sale. For example, if a company has no cash and a large amount of debt, enterprise value will give a much more accurate picture of a company’s value than using the share price. In practice, Templeton used the EV/EBITDA ratio to compare the real enterprise value (EV) to earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization. However, I would argue that EV/EBIT is a more accurate ratio, as it includes the costs of keeping the business running (depreciation of assets such as factories and amortization of intangible assets such as goodwill), but this is a matter of taste in the bigger picture.

- Another important metric for Templeton was the amount of a company’s debt. Both by using enterprice value, but also in its pure form. Templeton basically wanted to own companies that could make it through a recession or bad company news without the risk of not being able to pay its obligations. There are several ways to understand a company’s liabilities, including thoroughly reading the company’s balance sheet in the financial statements, including any notes that may exist on various liabilities. Templeton’s preferred ratio was net-debt-to-equity. That is, net debt to equity, which is calculated by taking: (short-term debt + long-term debt) – cash / shareholders’ equity. This ratio was also used by Benjamin Graham, who made it a basic rule not to own companies that owed more than they owned. In other words, we want a net-debt-to-equity ratio below 1.

Finally, it’s worth reminding ourselves that even a thorough and accurate valuation doesn’t tell us how far down the price of a given stock will go. Often, bargain hunters will buy stocks that continue to fall in value. That’s why belief in your own abilities and a healthy dose of patience are necessary character traits.

When should we sell a company?

OAlthough this issue has limited focus in the book, it is a difficult problem in practice and a topic that rarely gets enough attention. According to Templeton, as bargain hunters, we should have no problem ‘leaving money on the table’ and selling an investment before many others. There are two main scenarios where we should sell:

- When our stock has risen to a price above our estimated value of the company. Then it will be speculation and not investment. A concept also known as the ‘greater fool theorem’. Here Templeton is in line with his mentor Benjamin Graham’s approach in The Intelligent Investor. Since we can never be precise in our estimation of a company’s value, I believe we should sell when the share price is 15 or 20% above our estimate.

- When we find a stock that is a significantly better investment than the one we already own. This practice of comparing two specific investments is often easier than looking at an investment in isolation. Templeton’s main rule here is that we should only sell one stock to buy another when the new one is at least 50% better. A simple example can illustrate: If you own a stock with a share price of DKK 100 that you believe has a fundamental value of DKK 100 (the value is 0% above the price), you can buy another stock that is undervalued by at least 50%. If you find a new stock trading at a price of DKK 50, but you estimate the fundamental value to be DKK 75 (worth 50% more than the price), you should sell and buy the new stock.