Title: Zero to One: Notes on startups, or how to build the future

Author: Peter Thiel

Published: 2014

Buy the book here: Amazon

Why should I read it?

The primary target audience for the book is entrepreneurs who are considering starting a business. But the book is equally interesting for investors who want to understand the characteristics that need to be present to create a successful and sustainable growth company.

The book draws on Thiel’s extensive experience in the US tech sector, where he is one of the most successful entrepreneurs and investors. Thiel covers many different topics in the book, but of particular interest to investors is his model for building and investing in new technology companies.

The book is relatively short (just under 200 pages) and can be read by anyone with an interest in entrepreneurship and/or investing in growth companies, startups and venture capital.

Peter Thiel (born 1967)

Peter Thiel was born in Frankfurt, Germany in 1967, but moved to the US with his parents as an infant. His professional background is a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Stanford and then law. Before founding PayPal in 1999, he spent seven years as a law clerk at the U.S. Court of Appeals and an attorney at Sullivan & Cromwell.

eBay bought PayPal in 2002 for €1.5 billion. USD. Thiel then started a global hedge fund and subsequently Palantir Technologies in 2004, where he is still Chairman of the Board in 2021. In 2005, he founded Founders Fund with two former partners from PayPal, Ken Howery and Luke Nosek.

Follow the money

One of the most commonly used quotes in the investment world is attributed to Albert Einstein who said that compound interest is“the eighth wonder of the world”, and “the greatest mathematical discovery of all time” or even“the most powerful force in the universe“. The problem is that we don’t actually know if Einstein ever said any of these things, which just emphasizes one of the main points of Thiel’s book. There are very few people who are quoted decades or centuries after their death, but those who do are often quoted far more often than everyone else combined, think Shakespeare or Einstein. Or to take a modern-day investor – Warren Buffett.

“Whatever Einstein did or didn’t say, the power law – so named because exponential equations describe severely unequal distributions – is the law of the universe. It defines our surroundings so completely that we usually don’t even see it.”

In 1906, Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto discovered what we now call the“Pareto Rule” or the “80-20 rule”. He noted that 20% of the Italian population owned 80% of the land in Italy. Similarly, he noticed the phenomenon around nature, e.g. 20% of his pea plants produced 80% of the peas in his garden. We find examples of this phenomenon everywhere and the rule also applies in the business world, where successful companies achieve monopoly-like dominance in their respective markets and achieve greater value than millions of small undifferentiated competitors combined.

Compound interest – or more generally exponential growth – is a ‘power law’ that should be central to the way we run and invest in businesses. And the same is true for passive investors who want to become co-owners of companies that can achieve exceptional success. One or two companies will often become exponentially larger than all the others in the portfolio combined. Therefore, according to Thiel, we should only own the best companies that can create and maintain a monopoly in their market for decades. The second point is that we need to hold on to these companies over a long time horizon if we want to achieve the exponential returns that the few successful companies can provide.

It’s easier said than done in practice. The share price of a successful company will sometimes run significantly away from its fundamental value, which can lead to one or two companies in the portfolio being worth more than all the others combined. This will often go against many investors’ principles for limiting risk, e.g. a maximum of 5 or 10% in one company.

Such rules are recommended by many to ensure a sensible diversification (spread) across multiple companies and are sensible enough as a starting point. But if we want to create a return that truly outperforms the market, we have to let our winners run away. If we look at what many of the most respected investors in the world do, such as Warren Buffett, Li Lu or Guy Spier, they sometimes have 20%, 30% or even 50% in a single company. But they didn’t start out that way. They have been allowed to grow to this size, typically over a number of years and with a continuous focus on the development and potential of the business – and very little on what the share price is doing.

“The biggest secret in venture capital is that the best investment in a successful fund equals or outperforms the entire rest of the fund combined. This implies two very strange rules for VCs. First, only invest in companies that have the potential to return the value of the entire fund. […] two: because rule number one is so restrictive, there can’t be any other rules.”

Because we can’t know in advance which companies will be the most successful, we need to build a portfolio of companies with the potential to experience long-term exponential growth. For Thiel, every company in a good venture portfolio must have the potential to achieve massive success. In practice, this means that Thiel will typically have 5-7 companies in his portfolio. This is similar to the concentrated approach recommended by another well-known investor – Philip Fisher.

The last shall be first

In the book, Thiel makes an interesting comparison between the New York Times Company and Twitter. Here, Thiel uses data from the year the book was published (2014), but for fun, let’s try to make the comparison here in 2021, six years later. By mid-2021, both companies had around 5,000 employees and both offer people a medium to read their daily news. Times had an operating earnings of DKK 201 million. Twitter, on the other hand, has only started to turn a profit in the last couple of years and had a profit of USD 27 million in 2020 and has been profitable for the last 10 years, while Twitter has only started to turn a profit in the last couple of years and had a profit of USD 27 million in 2020. USD. Despite this, Twitter’s market capitalization is seven times larger than the Times. Why?

According to Thiel, the answer is cash flow and he makes a very convincing point. What defines an excellent company is fundamentally its ability to generate cash flow in the future. And there is a huge difference between the two companies. Looking at the companies’ top line, Times revenue has dropped from 2.1 billion euros to 2.2 billion euros. USD 1.8 billion in 2010 to USD 1.8 billion. While Twitter’s revenue has increased from 106 million USD in 2020 to 106 million USD in the same period. USD 3.9 billion to USD 3.9 billion. USD.

“Technology companies […] often lose money for the first few years: it takes time to build valueable things, and that means delayed revenue. Most of a tech company’s value will come at least 10 to 15 years in the future.”

Twitter was founded in 2006, but wasn’t in the black until 2016. Twitter is just one example among countless others. Another good example is Amazon, which only in the last five years has started to turn a bigger profit. One of the main reasons for this is that these companies have had owners with a genuine long-term perspective. For Amazon, this has meant that for countless years, Jeff Bezos has reinvested profits back into the business to drive future growth. It can therefore take many years before these types of businesses turn a profit. If you as an investor only look at P/E or Earnings Per Share (EPS), you will almost never be able to invest in this type of company. Does this mean that more value-oriented investors are excluded from these types of companies? Absolutely not, but it makes it difficult to make a valuation and investors should work with a wider range when assessing the company’s intrinsic value.

For a company to be valuable it must grow and endure. If you focus on near-term growth above all else, you miss the most important question you should be asking: will this business still be around a decade from now? Numbers alone won’t tell you the answer; instead you must think critically about the qualitative characteristics of your business”.

a modern monopoly

And what characterizes a company that can grow its cash flows far into the future? According to Thiel, all such companies are ‘monopolies’, i.e. companies that dominate their respective market. Every monopoly is unique, but often has a combination of the following characteristics.

1) Proprietary technology:

Technology ownership is the most material advantage a company can have because it makes its products or services difficult to copy. Take Google’s search algorithm, for example. It provides better search results with extremely fast response times and has a number of additional features such as a highly accurate autocomplete function, which helps protect the robustness of the service. According to Thiel, a good rule of thumb is that a company’s technology must be at least 10 times better than its closest competitor’s to lead to true monopoly status. The easiest way to do this is to invent a completely new technology, which could be a service that hasn’t been seen before (think Uber or Airbnb) or a new type of medicine. But it’s also possible to make improvements to existing solutions: Take Amazon, for example, which went from competing with traditional bookstores that might have 100,000 books to offering virtually all the world’s books in one place – at a lower price. It is also possible to gain monopoly status through product design, think Apple iPad versus Microsoft Windows XP tablet, or Motorola’s first smartphones versus iPhone 1.

2) Network effect

Network effects make a product or service more useful the more people who use it. The most obvious examples are the phone, the internet and social media such as Facebook. If all your friends are on, it makes sense for you to be on too. An interesting point is that companies building network effects need to start with very small markets and make sure they are successful there. For Facebook, it was Mark Zuckerberg’s fellow Harvard students who got their ‘blue book’ in an online format.

3) Economies of Scale

A monopoly business becomes stronger as it gets bigger. The company’s fixed costs of creating the product or service can be spread out over a larger number of sales, thereby improving the company’s margin. Think engineering, management, offices, etc. Software companies have a unique opportunity to scale without increasing costs. A good example is Microsoft Windows. Once the product is fully coded, a new copy will be at virtually no cost to Microsoft, but will have full value to the customer. A good growth business should have the potential to scale built into its design.

4) Branding

By definition, a company has a monopoly on its own brand, so creating a strong brand is an effective way to create a monopoly. Arguably the strongest brand over the past decade has been Apple, with their simple and aesthetic designs in everything from company logos and iPhones to flag ship stores and operating systems.

Eroom's law

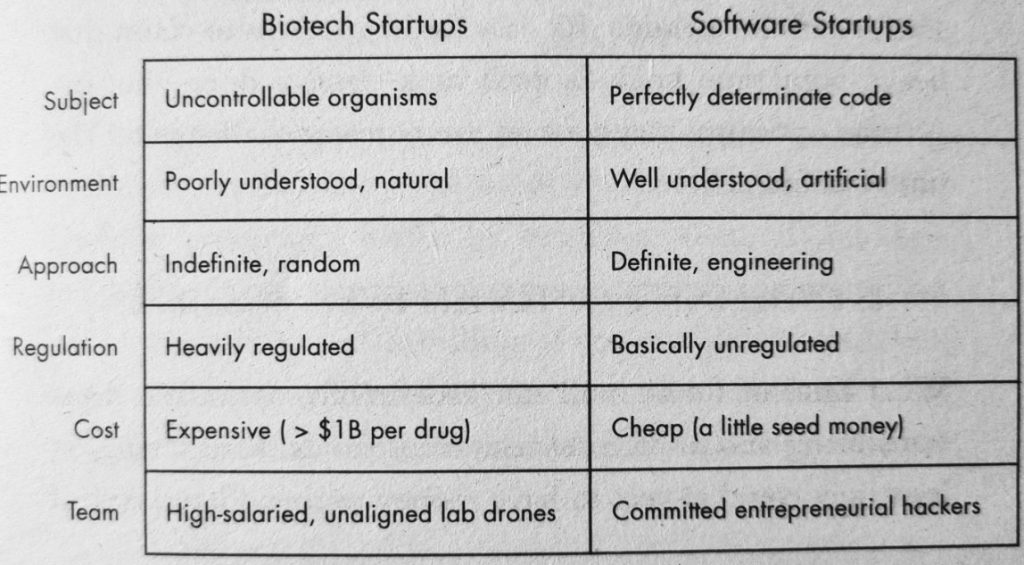

The four characteristics above can be present in many different sectors and industries. In a Danish context, where many growth companies are in pharma and biotech, Thiel has another interesting point.

Many of the major discoveries in pharmaceuticals and biotech over the last 100 years have happened by accident. Take Alexander Flemming’s discovery of a mysterious antibacterial fungus that had grown in a petri dish after he forgot to cover it in his lab. This led to the discovery of penicillin. Pharmaceutical companies today are trying to replicate Flemming’s circumstances by testing various more or less random combinations of molecular compounds in the hope of finding one that works.

The problem with this approach, however, is that it doesn’t work as well as it used to. Over the past decades, biotech has failed to meet the expectations of patients or investors. Eroom’s law – i.e. Moore’s law backwards – shows that the number of new medicines approved per billion The USD spent on research and development (R&D) has halved every nine years since 1950. In the table below, Thiel compares biotech and software startups, which is interesting in itself. But at the same time, the table and the topics in each row provide a good framework for investors to assess which sectors to invest in. I have no doubt which of the two I prefer.

Inspiration from Thiel's own portfolio in 2021

If we take a look at Thiel’s book, it is quite interesting as an investor that after his time at PayPal, Thiel founded the investment company Founders Fund with two former partners from PayPal, Ken Howery and Luke Nosek. This allows us to study the companies that Thiel himself has assessed as meeting his criteria and in which he has invested. Quite an interesting list to be inspired by.